GLM-5: from Vibe Coding to Agentic Engineering — Deep Technical Review (EN)

Author: zhongzhu zhou

Paper: GLM-5: from Vibe Coding to Agentic Engineering (arXiv 2602.15763v1, 2026)

ArXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2602.15763

Project: https://github.com/zai-org/GLM-5

TL;DR

- GLM-5 is best read as a full-stack agent-engineering system paper, not only a model-scale update.

- The strongest practical story is the combination of DSA long-context efficiency + staged asynchronous RL + realistic agent evaluation.

- Evidence is strong on engineering-oriented tasks, with clear progress over prior GLM generations and competitive standing vs proprietary models.

- Main caveat remains full external reproducibility at the same scale.

Estimated reading time: ~12–15 minutes

Abstract

I read the GLM-5 paper end-to-end and treated it less as a single-model report and more as a system paper across architecture, data, training infrastructure, post-training RL, and product-facing agent evaluation. My core takeaway is that the paper is trying to solve a concrete transition: from “vibe coding” (short-horizon, prompt-local coding productivity) to “agentic engineering” (long-horizon, stateful, environment-coupled software work).

Technically, the most consequential ingredients are: (1) DSA-based long-context efficiency, (2) asynchronous RL infrastructure and agent RL objectives, (3) explicit long-horizon evaluation (CC-Bench-V2 + SWE-rebench + chain tasks), and (4) aggressive infrastructure work to make the stack practical. The report is unusually broad: 40 pages, strong benchmark spread, and detailed engineering appendices. In this review I explain what GLM-5 does, the prerequisites needed to parse the claims, what I believe is genuinely new, where evidence is strong vs weak, and how one could reproduce parts of it in practice.

1) What this paper does

My reading is straightforward: GLM-5 is a full-stack release aimed at real long-horizon software agents, not a single isolated architecture trick.

The paper makes four high-level claims:

- Efficiency + scale claim: Use DSA and recipe changes to scale to a 744B total parameter MoE model (40B active) while preserving long-context quality.

- Post-training claim: Replace/extend synchronous RL pipelines with asynchronous, decoupled rollout/training systems and algorithms that are robust under off-policy drift.

- Agentic capability claim: Improve coding/tool-use/search behavior in realistic environments, not just static leaderboards.

- Deployment claim: Adapt deeply to domestic Chinese chips and optimize kernels/framework paths so the model is operationally practical.

I think the paper’s framing is strong because it acknowledges that coding benchmarks alone are insufficient. Their internal CC-Bench-V2 (frontend, backend, long-horizon chains) plus external benchmarks gives a more complete story than “one number on SWE-bench.”

2) Prerequisites I needed before digging in

Before I explain my judgment, I want to make my own reading assumptions explicit. If these prerequisites are missing, GLM-5 can look like “just a lot of benchmark numbers.” If they are in place, the system story becomes much clearer.

- MoE economics: total params vs active params, expert routing overhead, and communication bottlenecks.

- Long-context attention families: dense attention, MLA, SWA, linear variants, and DSA-like sparse retrieval.

- Speculative decoding + MTP: how accept length translates into practical serving throughput.

- RL update intuition: importance ratio, clipping, on-policy/off-policy drift control.

- Agent evaluation design: why pass@1 is insufficient for long-horizon, state-recursive engineering tasks.

2.1 What Muon means here (my engineering interpretation)

Let me explain this in a more basic way.

When we train large models, the optimizer is not only “a formula to update weights.” In practice, it is also a major systems component because it decides:

- how many extra states we must store per parameter,

- how much data must be synchronized across devices,

- how stable updates remain when training is noisy and long-horizon.

In this paper context, Muon is not just a cosmetic optimizer rename. The practical value is that optimizer behavior and distributed execution are co-designed so large-scale training is easier to run stably.

A simple intuition:

- Every parameter needs update statistics (e.g., momentum-like terms). Those states consume memory.

- In distributed training, these states/gradients must be communicated. Communication can become the bottleneck.

- If updates are too noisy or too aggressive, training becomes unstable.

So Muon-related engineering is trying to keep these three costs in balance: memory, communication, and stability.

From my perspective, this is exactly why the paper’s Muon discussion matters: it is a systems enabler, not only an optimization trick.

2.2 Why staged RL matters more than one-shot RL

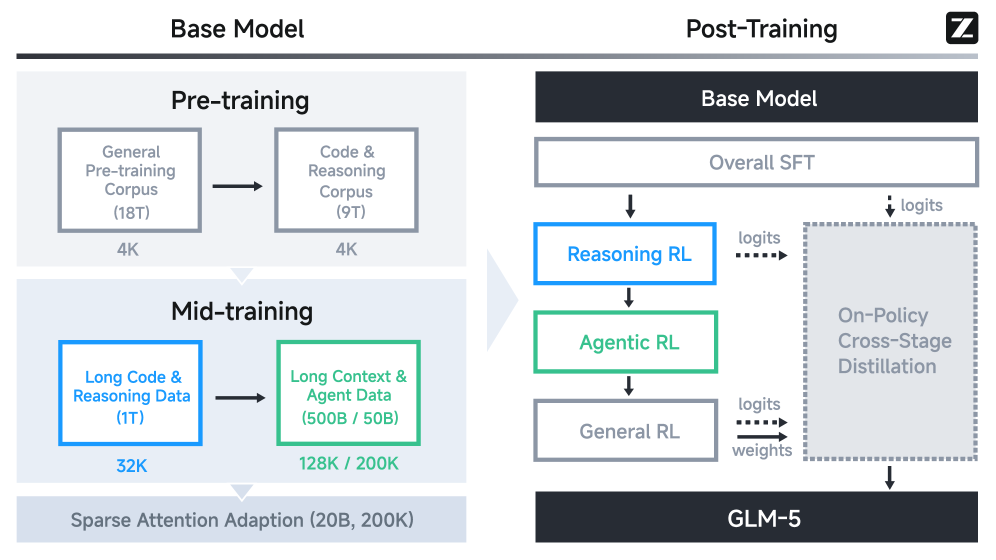

A lot of readers casually read “we did RL” as a single phase. I don’t think that interpretation works here. GLM-5’s pipeline is explicitly staged:

- Reasoning RL first (trajectory quality and answer consistency),

- Agentic RL second (tool use + environment interaction),

- General RL later (dialog quality, style, emotional alignment).

This staging is one reason the report feels internally coherent: each phase targets a different failure mode.

2.3 Sync RL vs async RL (why they moved)

In my own words: synchronous RL is simple but wastes compute in long-rollout settings because fast workers wait for slow trajectories. Asynchronous RL decouples rollout and optimization, so utilization is better.

The cost is policy staleness (off-policy drift). That is exactly why importance-ratio control and clipping become operationally central, not theoretical decoration.

2.4 PPO/GRPO-style intuition in plain language

The practical intuition I use is simple:

- increase probability of high-reward trajectories,

- decrease probability of low-reward trajectories,

- use ratio/clipping to avoid unstable oversized updates.

So the hard part in GLM-5 is not “having an RL formula,” but keeping updates stable under asynchronous, noisy, tool-interactive long trajectories.

2.5 Quick concept glossary (basic but important)

- MoE (Mixture of Experts): only part of the network is activated per token, so total parameters can be huge while per-token compute stays lower.

- Active parameters: the subset of parameters actually used for one forward pass.

- DSA (Dynamic Sparse Attention): an attention strategy that retrieves/selects relevant context instead of attending densely to everything.

- MLA: a memory-efficient long-context attention design used as a strong baseline in this paper.

- SWA (Sliding Window Attention): restricts attention to local windows; cheaper but can lose very long-range dependencies.

- MTP (Multi-Token Prediction): predicts multiple future tokens, often used with speculative decoding to improve throughput.

- Accept length: in speculative decoding, how many drafted tokens are accepted on average; higher usually means better decoding efficiency.

- GRPO/PPO-style update: RL policy update with ratio/clipping mechanisms to reduce instability.

- On-policy vs off-policy: whether training data comes from the current policy or from older policies/logged rollouts.

- Policy staleness: mismatch between data-collection policy and current training policy in async pipelines.

- Distillation: training a target model to imitate a stronger teacher/trajectory distribution for capability recovery and compression.

- BSR / ISR / CSR: build success rate / instance success rate / checklist success rate for agent task evaluation.

- Pass@1 limitation: single-shot correctness metric; often misses long-horizon consistency and interaction failures.

3) Method details — my technical reading

3.1 Pre-training architecture choices

From model size table, GLM-5 moves from GLM-4.5’s 355B total / 32B active to 744B total / 40B active, with fewer layers (MoE layers 89→75) and larger hidden dimension. My interpretation:

- They traded depth for larger expert scale and reduced communication overhead.

- This likely helps throughput and engineering stability on large clusters.

- The bigger active parameter budget (40B) should help per-token quality, especially on coding/reasoning.

MLA adaptations and Muon Split

In Table 1, they show baseline comparisons among GQA-8 and MLA variants.

| Dataset | Hellaswag | MMLU | C-Eval | RACE | BBH | GSM8K | HumanEval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GQA-8 | 77.3 | 61.2 | 60.0 | 79.6 | 53.3 | 47.6 | 38.5 |

| MLA | 77.3 | 61.5 | 59.7 | 77.8 | 48.9 | 46.2 | 33.5 |

| MLA + Muon Split | 77.8 | 62.5 | 62.1 | 79.9 | 51.8 | 45.0 | 36.7 |

| The key point I took away: plain MLA with their optimizer regime underperforms some GQA metrics, and Muon Split appears to recover much of the loss. |

This detail matters because many papers present attention substitutions as “plug-and-play.” Here, the authors are explicit that optimizer/parameterization coupling is non-trivial.

MTP parameter sharing

Table 2 reports accept length improvement (DeepSeek-V3.2: 2.55 vs GLM-5: 2.76 in their setting).

| Model | Accept Length |

|---|---|

| DeepSeek-V3.2 | 2.55 |

| GLM-5 | 2.76 |

As an engineering note, I view this as “small per-token wins that compound at scale.”

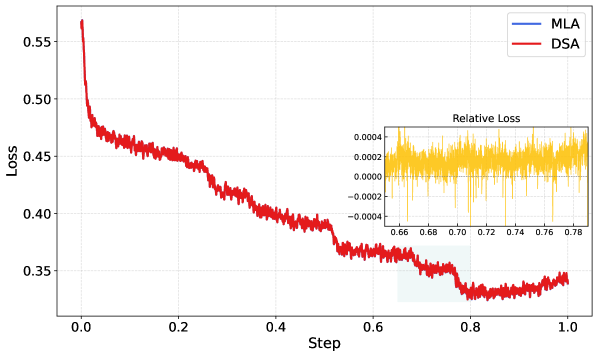

3.2 DSA continuation strategy

The paper does not merely say “we used sparse attention.” It reports a continuation recipe:

- Start from a dense/MLA-trained checkpoint.

- DSA warmup (indexer adaptation).

- Sparse adaptation stage with additional token budget.

In Table 3, long-context benchmark differences between MLA and DSA are close (and mixed in direction), which supports their claim that DSA can preserve quality while cutting long-context compute.

| MQ-NIAH-128k | MV-NIAH-128k | SQuAD-128k | HotpotQA-128k | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLA | 100.0 | 95.5 | 79.7 | 66.3 |

| DSA | 100.0 | 97.0 | 86.0 | 63.0 |

The ablations in Table 4/5/6 are among the most valuable parts of the paper for me:

- Table 4: naive SWA interleave collapses quickly at longer lengths; search-based pattern helps a lot.

| 4K | 8K | 16K | 32K | 64K | 128K | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLM-9B (Full Attn) | 95.19 | 93.67 | 92.01 | 91.09 | 85.35 | 75.28 |

| SWA Interleave | 94.87 | 54.02 | 25.89 | 12.61 | 8.32 | 6.51 |

| SWA Pattern | 95.78 | 92.54 | 88.92 | 82.52 | 70.23 | 53.95 |

| - Table 5: even better efficient variants still show retrieval/task losses at very long lengths. | ||||||

| - Table 6: DSA warmup-only has a long-tail penalty at 128K, but joint training largely closes it. |

My read: the paper’s strongest pre-training argument is not “DSA is universally superior,” but “lossless sparse retrieval with proper adaptation can avoid the severe quality cliff seen in naive efficient attention substitutions.”

3.3 Data and mid-training strategy

The base model budget is reported as 28.5T tokens overall across stages, with mid-training context progression to 200K. I liked that they discuss:

- code corpus expansion and low-resource language classifiers,

- long-document filtering and anti-synthetic controls,

- repo-level software engineering construction (issue/PR/file context).

Even though exact dataset release is unavailable, the conceptual design aligns with their downstream emphasis on long-horizon engineering.

3.4 Training infrastructure contributions

This section is underrated. For large models, “algorithmic contribution” without systems support is often non-deployable.

I noted five pragmatic pieces:

- Flexible MTP placement to reduce stage imbalance.

- Pipeline ZeRO2-like gradient sharding and buffer reuse.

- Zero-redundant Muon communication paths.

- Activation offloading + recomputation overlap.

- Sequence-chunked projection/loss to reduce peaks.

None of these alone is novel in isolation, but as a combined recipe, they explain how the training plan remains feasible.

3.5 Post-training RL stack

The post-training path is staged: SFT → Reasoning RL → Agentic RL → General RL → on-policy cross-stage distillation.

Reasoning RL

They build on GRPO + IcePop-like mismatch handling and explicitly separate training/inference policy distributions. I appreciate that they surface a very practical DSA RL stability issue: non-deterministic top-k behavior can destabilize RL quickly. Their choice to use deterministic torch.topk despite speed cost is a strong “engineering honesty” moment.

Agentic RL

This is central for the paper’s theme. Synchronous RL with long rollouts creates GPU idle time; they decouple rollout and training via orchestrators and add token-level clipping-based off-policy control (double-sided importance sampling style).

In plain words: they are optimizing not just policy quality but end-to-end RL system throughput.

General RL + human style anchoring

They split objectives into correctness, emotional intelligence, and task-specific quality with hybrid rewards (rules + ORMs + GRMs), and mention explicit use of high-quality human responses as style anchors. I view this as consistent with current best practice for avoiding over-formulaic model tone.

4) Experiments and benchmark setup

Before diving into sub-sections, the paper’s end-to-end training architecture is best read directly from Figure 5, because many benchmark outcomes later are consequences of this staged design (pre-training, long-context mid-training, staged RL, and cross-stage distillation).

4.1 ARC benchmark panel

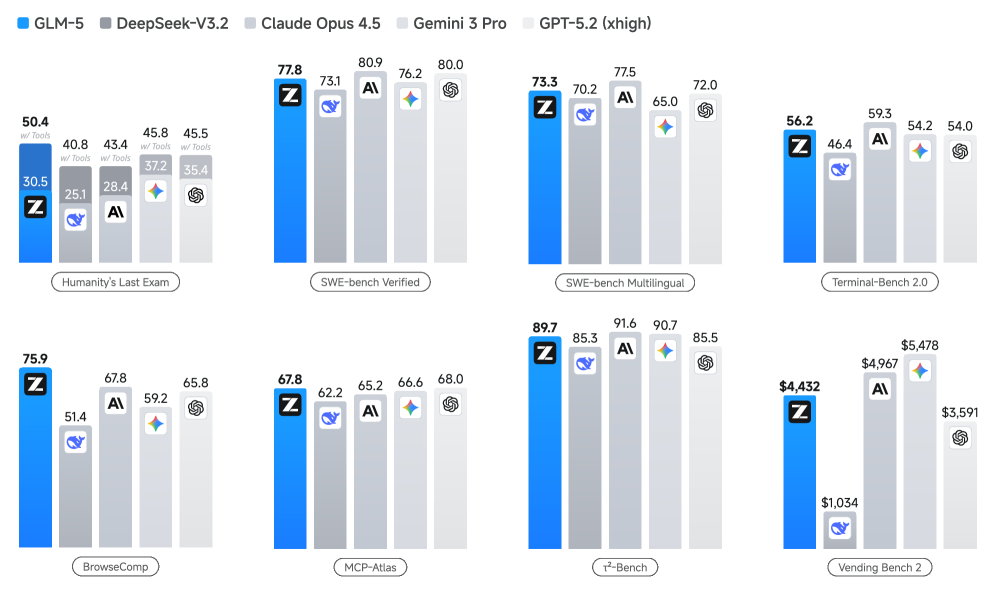

The main comparison table is main ARC results table. I consider it one of the most informative multi-axis summaries in recent model reports because it spans:

- Reasoning/general (HLE, AIME, HMMT, GPQA, LongBench v2),

- Coding (SWE-bench Verified, SWE-bench Multilingual, Terminal-Bench, CyberGym),

- Agentic tasks (BrowseComp, τ²-Bench, MCP-Atlas, Tool-Decathlon, Vending Bench 2, GDPval-AA).

From main ARC results table, GLM-5’s pattern is:

- Strong jump over GLM-4.7 in most categories.

- Competitive with top proprietary models on many tasks.

- Not uniformly best across every benchmark.

I appreciate that this pattern is realistic; single-model dominance across all categories is rare.

4.2 Internal real-world suite: CC-Bench-V2

CC-Bench results table + Figure 10 are critical. The frontend evaluation pipeline introduces “Agent-as-a-Judge”: build verification + interactive GUI exploration with pass/fail checklists. The paper reports high pointwise agreement with human experts and strong ranking correlation.

What I like:

- It evaluates visible, interactive correctness, not just static outputs.

- It includes multiple stacks (HTML/React/Vue/Svelte/Next.js).

- It distinguishes BSR/ISR/CSR, so we can see where failures happen.

From CC-Bench results table, GLM-5 has high build success and improved CSR, but ISR still trails Claude Opus 4.5 in key stacks. My interpretation: GLM-5 often does many parts correctly but still misses full end-to-end closure.

4.3 Long-horizon engineering and evolving tasks

The long-horizon chain design is compelling: state-recursive multi-step tasks where each step changes repo state and errors compound.

This addresses a known blind spot of single-commit benchmarks. If a model is good at local edits but poor at maintaining consistency over a chain, normal pass@1 can hide it.

For freshness/generalization, SWE-rebench table (SWE-rebench) gives evolving task performance. GLM-5 improves vs GLM-4.7 but remains behind top proprietary entries. I see this as evidence that the paper’s “agentic engineering” goal is directionally successful but not solved.

5) Results interpretation — where I think the evidence is strongest

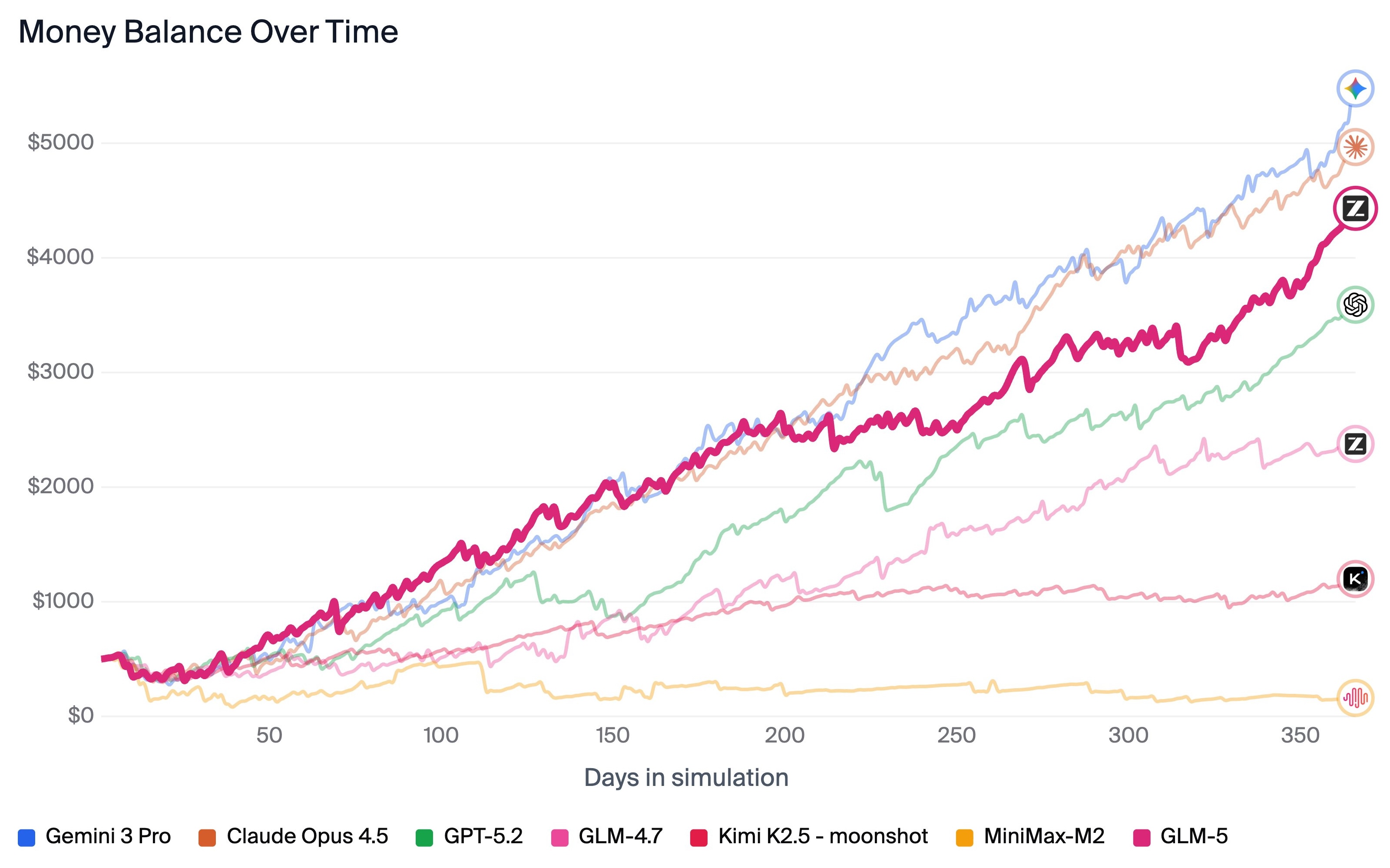

5.1 Figure/Table analysis #1: Figure 1 (8 benchmark radar-like summary)

In Figure 1, GLM-5 is presented against GLM-4.7, DeepSeek-V3.2, Claude Opus 4.5, Gemini 3 Pro, GPT-5.2 across 8 agentic/reasoning/coding tasks.

My take:

- The broad uplift over GLM-4.7 is consistent and not tied to one benchmark family.

- GLM-5 appears to close significant portions of the proprietary gap, especially in coding/agentic tasks.

- The profile suggests a balanced model rather than a narrow specialist.

5.2 Figure/Table analysis #2: main ARC results table (ARC main table)

main ARC results table gives the granular story behind Figure 1. I interpret it as follows:

- Coding results are among the strongest signals (SWE-bench Verified/Multilingual, Terminal-Bench variants).

- Agent benchmarks show strong progress, especially with context management and multi-tool setups.

- Reasoning metrics are competitive but heterogeneous, with proprietary models still leading in some scientific/deep-reasoning slots.

This distribution matches what we would expect from a pipeline heavily optimized for engineering agents.

5.3 Figure/Table analysis #3: Table 5 (efficient attention ablation)

For me, Table 5 is a “trust-builder.” Instead of only showing the winning setting, they quantify losses in alternate efficient attention variants across multiple long-context benchmarks.

| Method | RULER | MRCR | HELMET-ICL | RepoQA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLM-9B | 85.35/75.28 | 36.53/35.39 | 77.68/77.36 | 69.00/65.83 |

| SWA Interleave | 65.94/44.93 | 30.03/28.83 | 75.96/63.52 | 50.33/39.33 |

| SWA Pattern | 83.72/69.59 | 35.02/33.58 | 76.48/74.60 | 62.33/51.17 |

I read this as: the team understands the failure modes and is not hiding trade-offs. For practitioners deciding architecture, this ablation is more useful than top-line SOTA claims.

5.4 Figure/Table analysis #4: CC-Bench results table + Figure 10 (CC-Bench-V2)

These are perhaps the most product-relevant artifacts:

- Figure 10 formalizes a reproducible-ish frontend judging protocol.

- CC-Bench results table separates buildability from true task completion.

The ISR gap despite high BSR is especially important. It tells me “code compiles” is no longer enough as a success metric for agentic coding systems.

5.5 Figure/Table analysis #5: SWE-rebench table (SWE-rebench)

SWE-rebench table gives a more forward-looking check by using newer mined tasks. GLM-5’s gains over GLM-4.7 are present but modest compared with top proprietary peers.

This is exactly the kind of realism I want: progress is substantial, but frontier competition remains tight.

6) Limitations and boundary conditions

I see at least eight limitations/boundaries:

- Reproducibility depth: no full data/model release recipe for 28.5T-token pipeline, so exact reproduction is currently impossible for most labs.

- Evaluation dependence on internal suites: CC-Bench-V2 is insightful but not yet a fully community-standard benchmark.

- Judge-model risk: agent-as-judge and model-based evaluation can inherit judge biases despite reported validation.

- Async RL complexity: decoupled systems are operationally harder; small teams may struggle to replicate stability.

- DSA implementation sensitivity: deterministic top-k observations imply kernel/operator details can make or break RL behavior.

- Cost opacity: paper emphasizes efficiency but does not provide complete training FLOPs/cost decomposition.

- Long-horizon still unsolved: chain tasks still show notable gap to top proprietary systems.

- Security/safety details limited: for real agent deployment, safety instrumentation details (policy/runtime guards) are relatively brief.

7) Reproducibility and engineering notes (practical)

If I were trying to reproduce the spirit (not full scale) of this work, I would structure it in layers:

7.1 Minimum reproducible stack (research group scale)

- Base model: 7B–32B open MoE/dense model with long-context support.

- Attention study: dense vs SWA-pattern vs linear variant vs DSA-like sparse retrieval adaptation.

- RL infra: start synchronous first, then decouple rollout/training with explicit telemetry.

- Benchmarks: SWE-bench-lite + Terminal-like tasks + one internal long-horizon chain dataset.

7.2 Key instrumentation I would insist on

- per-stage GPU utilization during RL,

- rollout/training lag and policy staleness histograms,

- deterministic/non-deterministic operator flags,

- long-context retrieval diagnostics (miss rate vs context position),

- chain-task error propagation traces.

7.3 Engineering pitfalls suggested by the paper

- Treat top-k/indexer determinism as first-class, not optional.

- Do not trust build success as task success.

- Expect asynchronous RL to need better observability than classic PPO loops.

- Maintain cross-stage distillation or equivalent anti-forgetting mechanism if multi-objective RL is sequential.

8) How this paper connects to the field

I place GLM-5 in a trend where model progress is increasingly systems + data + objective design, not just larger pre-training runs.

Relative to many model reports, GLM-5 gives unusually concrete evidence that “coding agents” should be evaluated on multi-step stateful execution and GUI/interaction correctness, not only static patch-level tasks.

I also think the DSA + async RL combination is strategic: one reduces long-context compute burden; the other turns saved/system-available capacity into more rollout diversity and faster iteration.

9) My final assessment

My bottom-line judgment (in my own working style):

- Strong paper for practitioners building coding/agent systems.

- Most valuable contributions are integrated engineering choices, not a single theorem-level novelty.

- Evidence quality is good across multiple benchmark families, with useful ablations.

- Main weakness is full external reproducibility due to scale/data/infrastructure constraints.

If my goal were to improve real-world engineering agents, I would absolutely study this paper carefully. If my goal were strict algorithmic novelty in isolation, I would treat it as a robust systems-integration report with selective algorithmic additions.

References

- GLM-5 Team. GLM-5: from Vibe Coding to Agentic Engineering. arXiv:2602.15763, 2026.

- Related citations are discussed according to the paper’s own bibliography and benchmark references.